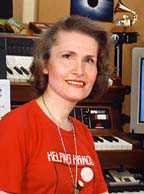

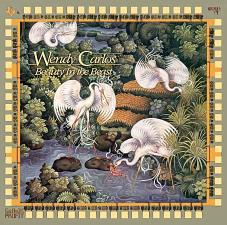

In this multi-faceted 5-section interview, electronic music pioneer Wendy Carlos reveals not only her techniques at working with digital sound synthesis, but shares her views on Art, Composing, micro-tonal scales and the curious spirit. The Digital Transition Carol Wright's phone interview with Wendy Carlos took place on Saturday, December 2, 2000, shortly after the rerelease of her newly remastered Digital Moonscapes (1984) and Beauty in the Beast (1986) [see the reviews], two albums as firmly entrenched in digital synthesis as her Switched-on albums were in the Moog's analog world. Wendy settled into her Village loft recording studio for a long interview, and they discussed Thai food and the ongoing follies of the presidential election as Carol, a continent away on Orcas Island, Washington, tested her phone transcriber. Carol Wright: Just a minute. Let me make sure it's recording. [Stops recording and plays back test.] Okay, I heard voices so... Wendy Carlos: Are you hearing voices? I know a good shrink if you're hearing voices. She has a special salon every Monday evening for Joan of Arc wannabees. Carol: [Laughs] You can do that all you want. I'm immune to your teasing. Wendy: I'm sorry, just being silly. My Mysticometer kicked in. I sensed that. Wendy: Well, we could joke all night, but why don't you ask me the questions you had lined up for the Synthmuseum. So, first the usual disclaimer that I don't have the expertise of someone who is a keyboard artist, composer, or techhead. However, I've survived two interviews with you, so that should qualify me. Wendy: You bet! But your questions instinctively look into other areas instead of the same old retreads, both people bored with each other. No, I don't think that will happen. Carol: Okay, here we go.

The Digital TransitionCarol: You spent a good ten years or more building and improving your state-of-the-art analog Moog studio, with assorted vocoders, and what not. When did you first get wind of the digital future? Did you look at your studio and think "gotta start all over"? Or were you anxiously waiting, the first in line? Wendy: I wish I could give you a sound bite answer on this. For most of my years, I was aware of using digital as a music tool. My first experience was at the Columbia/Princeton Center, where they had a tie--in to university's computer facility. I had messed with that with another composer-techhead, but computers were so primitive I realized that digital was not the way to go for the time. Even the Center's big legendary RCA Synthesizer was an analog machine. So the answer for me was to go with Bob Moog's analog devices. Finally, the middle '70s, Rachel Elkind (my producer then) and I went to Dartmouth to see a computer music installation that lead to the Synclavier, a very expensive system that was popular in the '80s. It was kind of thin, then, not very much meat on the bones. In 1977, we decided that since no one seemed to be doing anything digital--and we had just a little money in the bank--we hired an engineer to build a digital synthesizer prototype. (I still have part of it in the loft here). It was an amusing device, but we didn't have the money or the staff to develop it further, or market it. It's foolish for a composer to try to do that on his or her own. We saw the Bell Laboratories setup in New Jersey, and looked at another digital device like the Fairlight, which was sample-oriented--quite limited--but popular with rock and roll musicians whose needs were not seriously involved with synthesis. If they could get drum samples, it served their purpose. I'm not putting it down, but from the point of view of a synthesis, and of a serious composer, it was slim pickings. The one that caught my eye, however, was the Crumar GDS, which stands for General Development System. This was the prototype for a simpler machine called the Synergy, by coincidence the same name Larry Fast's used for his recorded performances. The GDS/Synergy was a machine I got very deeply involved with in 1981, my first significant involvement with a digital machine. I think it is still superior in certain areas to the machines that have come out since. Sorry, but in certain areas, it remains superior. No one else has bothered to do some of the things the Synergy could do. Yes, others have done it quieter, with greater fidelity, better high frequencies, and less hiss. But they have not developed the real difficult tasks, like full additive synthesis with complex modulation. So out of that came Tron, Digital Moonscapes, and Beauty In the Beast.

Any other units you throw into the mix in those days? Yamaha came up with the early '80s DX model (not quite as good as the Synergy), and in 1990, they manufactured the fine SY77, which I still use. It's somewhat cleaner sounding than the old Synergy. Finally Kurzweil came out with some excellent hybrid models that involved both samples and synthesizer technology. My involvement with digital is not a single event that led me down a single path. It spread throughout my work in this field and has many cul de sacs of participation and interest I've gone through the last forty years. I've probably forgotten more than I know now on the topic. So, what do you want from me, already? It's a big, bulky, disorganized subject. I haven't thought it through, nor have I spoken with any one about this until you asked the question. And eventually you incorporated MIDI controllers and samples. I started with MIDI in the mid-'80s. Dave Smith--a charming, bright guy--invented it in '83, and got the Japanese companies interested in it when the Americans were going "NIH! NIH!"--not invented here. There is some use of MIDI on Beauty In the Beast: combinations of sounds are very often tied together with MIDI, but not using the advanced features. Then the Peter and the Wolf project was entirely MIDI, using the computer as a recording device for the individually performed parts, the first time I did that. So my Macintosh was where I polished all of the performances, then it cranked out the notes, and I recorded them all on tape, one note at a time, just like I did with Switched-On Bach, but I drove the sounds with the computer. And that's the slowest and most difficult way I've ever had to work, a tedious project.

Then my most recent album, Tales Of Heaven Tales of Heaven & Hell, has a lot of MIDI, and musique concrète--live singers, some percussion, sound effects--recorded on hard disk using Digital Performer. All of my newer stuff that I'm tinkering with uses the computer as a tape machine, as a MIDI machine, and to tinker with the individual sounds. So, the computer becomes a Swiss Army Knife. In the 1970s, Rachel Elkind and I used to dread going down into our basement studio, because nothing changed. It was frustrating to keep using the Moog synthesizer; it's not good to keep the same static stuff going. If you write for an ensemble, you will try different groupings: string quartet, quintet, orchestra, chorus, or piano solo. You have to keep it interesting--I feel you do, anyway. But in the '80s, I had lots of options: I used some of the Moog, some of the Synergy, the Yamaha, the Kurzweil. Now, in the '90s, progress has been a little static again. I mostly use the Kurzweil K2000, a modest, inexpensive, excellent instrument, very clean. And I've gotten involved with the Korg Z1, which is fascinating in a different way. You can model acoustic sounds with it, very flexible and expressive to play. I've always had a variety of technologies here, and I don't much care which tool I use. If it cuts the wood and drills a nice clean hole, I use it. I just wish that the job that began with the Synergy would be picked up again and would move in the direction of real, profound synthesis. But no one seems to care about that any more. Just whatever is obvious and easy. So it's a shame. I think I'll die before the next step is taken. So is what has happened is that the music world has settled for samples? Wendy: Yes, and prerecorded rhythm samples. That's just like an artist using clip art. It's fast, and a lot of the young people involved in the field don't know the background. They think MIDI loops and samples and groove boxes are it. Just curious: Isn't it somewhat annoying to learn one system and then have to master another whole technology? Wendy: Changing equipment and approaches is always somewhat of a struggle and a nuisance. The composers before us didn't have to reinvent themselves all the time. I've had to work horizontally with different instruments, but also vertically to change the whole way to control them. It's like having to master the violin well, then deciding to be a mezzo-soprano or play the oboe. You can waste your whole life trying to move into too many directions. Just getting the breadth of the instruments you are proficient in ought to be enough.

However, most of the folks using electronic instruments don't seem to me to move much at all. We are given a range of technologies, but so many are standing on the one square foot, and few are moving off of it. And they don't even seem to know or care, ignorance and apathy. The king is naked--there, I've said it! Where are the curious? Do you notice if people are curious these days? I don't see many curious people among the composers and musicians. For example, why be satisfied with just the same old Equal Tempered scale? Why not fool with alternative tunings? It's such a simple thing--much of it is very worthwhile--you don't even have to do very much. I rant on this one all the time. I guess I am just an old opinionated curmudgeon, but I don't understand such conservative values in an artist. You don't want to lose your curiosity. It defines you as a person in some way. Well, this has nothing to do with your questions, but is a philosophic question of a Life Quest. I'd like to see a little more interest in these topics than "inquiring minds want to know," which is exactly 180 degrees from what that really means. People just seem to wallow in what they already know. Jeepers. Inquiring mind wants to know: Where were we? Wendy: You asked me about when I became involved in digital, was it a big revelation and did it shake up my ability to work? Actually, it was annoying to have to learn a lot about it, but what is more annoying now is when new instruments come out that are effectively the same thing, but you need to learn new techniques to do them. Software is often like that, too. But with a new computer graphics or animation program, you will have to learn something new, but you'll get something new back. That's a fair trade.

Do any consulting or beta testing? Wendy: I used to consult and beta test for quite a few music and synth companies. But a lot of my friends there have left now, and many of the companies just haven't moved on. A notable exception is Mark of the Unicorn, which created a Mac music audio software program, Digital Performer. I respect what they have done, and have worked with them off and on for over 15 years. Your two re-releases feature digitally synthesized instruments--the LSI Philharmonic for Moonscapes and the exotic instruments of Beauty In the Beast--that you crafted yourself. For those new to electronic music, what exactly does it mean to have digital sound versus analog sound? Wendy: Digital, of course, is essentially computer data which accurately describes an audio signal. It's easily manipulated and can be copied exactly--all those ones and zeros, you know. Analog is how we usually describe sound waves, a continuous change of pressure or an electrical signal, what a microphone produces, what we used to record on tape. It's a much riskier way to handle audio, but historically was the method we first discovered. Between the two, don't look for deeper meaning or arbitrary differences. There is a cult of near-religious dogma that proclaims analog sound on LPs to be perfection (what a hoot that is for those of us who used to cut LPs for a living!). They think you have to use special wires and elaborate techniques they don't even understand, and they claim that digital is in cahoots with Lucifer. It's kind of pathetic, based on ignorance and flamboyant cheek. The simple answer for synthesizers or reproduction is: To the listener, it shouldn't matter at all, as long as it sounds fine. If you're a performer, it shouldn't matter at all. If you have a very advanced analog synthesizer and then you have another that is all digital--and you get a lot out of both--fine, use it. On the other hand, digital can, in principle, let you be more precise, with finer finesse and control. Analog runs out at five significant digits of accuracy, something like that, and there's tape hiss to contend with. If you want to put the money and time into it, you can obsess with digital until you're dead. It's a potential that hasn't often been tapped, but usually you reach a practical limit, there's life for you. Microtonal tunings are a breeze with digital synthesizers, but very hard to do with analog. With digital, can you take the finished mix, and where you've recorded a cello, perform a global search-and-replace to substitute refinements, to just that digital instrument? Or change the cello to a trumpet? Does the digitally created instrument offer that kind of possibility after you've composed and mixed? Wendy: Once recorded, no matter what kind of machine, the signal is pretty hard to change, except in broader ways. A real synth may combine just sawtooths and pulses and sines (like a Moog), or may use recorded waves (like the Kurzweil's), not unlike a sampler. But the big point is that you can then build instrumental timbres with attack and decay and filter controls, wave shapers and manipulators, a whole mess of others. But once a performance is recorded using such "flexible" instruments, you're back to having a mere recording, a signal that no longer has the control that the instrument provided.

Not even with Digital Performer, when all the parts are recorded separately on the computer? Wendy: They have a lot of cool tools, but you're still best off making those changes before you record the performance. Since a sound sample is a digital signal, can you have the same degree of control as a digital sound you've built from scratch? Wendy: No, not in general. Samples use digital for recording and playback--but not for the potential power of digital synthesis. Samplers hearken back to the days of the Mellotron and Chamberlain. The reason I use the Kurzweil 2000/2500 is that they give you synthesizer manipulation on top of samples, and they sound wonderful. You can make your sounds working with the samples' waveform instead of a raw sine wave or sawtooth. The Kurzweils don't have the breadth and depth that the Synergy was exploring, while, the Synergy couldn't do samples. If you put all those things together, you'd have something pretty remarkable. So far nobody's done it. Again, from the audience point of view, it shouldn't matter at all. If you are hearing something very subtle, sophisticated and beautifully shaped, it's probably more likely to be coming from the newest digital stuff. But not necessarily. In the end, I listen, and if something sounds good, I use it. Crafting Digital Replications

Carol: When making a digital replication of a sound--the LSI Philharmonic instruments in the case of Moonscapes and exotic instruments for Beauty In the Beast--did you use recordings of real instruments for reference? Wendy: I did. I have a few LP collections of "this-is-the-orchestra" kinds of things. But when I went into this, I had a lot of other musical experience, too--twenty years with real instruments, a lot of study, and all the learning that went on with the Moog. I had an idea on how to go about trying to build a digital replica, and I stumbled around until my ear was satisfied. Hearing Digital Moonscapes recently, I'm aware that the replications are not perfect. It's like computer graphics, like a depiction of a forest with computer animals running in it. It's not exactly not like the real thing, and ironically, the closer you get, the more you're aware of any remaining differences. I think the early Moog replications of the orchestra that I did were very far off, but people accepted them. Now, some people really hated the LSI Philharmonic digital replications. I don't think they are actually bad--they are much closer than what I did with the earlier Moog records--but they come close enough that you are aware of the differences. Ironic, isn't it? Now the Kurzweil, though based on samples, doesn't sound like an orchestra either. You must tinker with the samples too, if "reality" is what you're after. But then after you've learned all that, what you should be doing is to extend it, extrapolating it to other directions, based on the good orchestra sounds that exist. That's what I try to do, anyway. If your digital replicas are so versatile, why are you now using samples rather than your own digital sounds? Wendy: I don't have a synthesizer that does all that I want it to do. I can go back to the Synergy, and probably will some on the next album, but it's kind of clunky and dated. You can play only a few notes at a time, and you can't mix a sample in with it. The Yamaha SY77 has its own features, can use both ideas, so I frequently work with it. The Kurzweil contains a good synthesizer plus excellent sampling, so I'll work with that, too. But to answer your question: I do what I can do. I want to saw a square hole, but I have only a round drill. So, you approximate or approach it. Anything cool on the horizon? Wendy: I no longer kid myself. I don't think that we'll make any progress soon and haven't really in the last decade. I suspect the progress phase is over. I was born into a moment of history that I could pioneer a few things, but at the other end of my life I'm going to reach a cut off before the meaty, powerful "anything you can imagine" processors are available. And that's sad. I wish it had all been squeezed into a fifty-year life span of productive work. But it didn't happen that way, and probably won't happen soon enough. Right now, we don't have a paved freeway to the really new sounds. You have to make do with decent covered wagons. It's a time consuming method--I've always done it the hard way, but now am getting impatient. So, using your 1982 Synergy digital processor--and not samples, not MIDI--for Digital Moonscapes, you created orchestral instruments. A real violin section has a variety of instruments, bows, rosins, different tonal qualities for each player. Did you make more than one violin replica to help create richness within the section? Wendy: Yes. Bunches and bunches. To what lengths did you go to get as much variety as possible in each instrument group?

Wendy: When you're creating these sounds, you're likely to sense something missing, so you try a variation on it. Then you come back the next day you discover it wasn't so much better, just different. Each replication has its strength and weakness, so I combine all my variations. I do that with all the sounds I create. How do you decide when to cut loose and say "the hell with it, that's as good as I can get it"? From the point of view of "sounds," I have never been satisfied with sounds--anyone's--of any kind--ever! It's too easy to notice the holes. If the goal is to create Art, then it doesn't matter one whit. If you were painter like Picasso in your "early blue period," you painted two musicians sitting under a tree with moonlight shining on them. And it really didn't look exactly like moonlight and the shadows were not exactly the color of real life. So what? But from a music instrument builder's point of view, I always want to get it better, reach the peaks of the best acoustic instruments. So there's a duality. Did you create your violin section from massing individual instruments or did you create a "whole section" sound? Wendy: Both ways in combination. I made some that sounded like solo violin, others that sounded like four or five playing together, and varieties of those. So I'd mix violin A with violin group D and so forth and the same for the other instruments--cellos, varieties of French horns--all through the orchestra. I discovered that some replicas were better playing staccato passages, others better at long, single tones. You end up saving a lot of variations. I don't see that as a problem. When you write an orchestral score, you instruct musicians to play in different ways. A bow can play normally or col legno, which means with the wood, or sul ponticello, bowing near the bridge. There are lots of little bits synthesized performance business that are similar variations. You just don't have an Italian word to hang on it. However, I don't find any electronic sound to be as rich as I can get with acoustic instruments. All of the digital replications of the LSI are to me approximations of the ideal values. Like computer graphics, we're getting closer, and it's amazing what's been accomplished.

At age 25, I took up the cello and the violin--and really know what it sounds like to start a bow against the string. I thought I heard on Moonscapes that each bow stroke had a bite to start off the note. Wendy: I worked very hard for that. Thank you for noticing! That was difficult. Nowadays you might hear it from a sample with mike placed within one inch of the string so you record this gristly sound--a terrible caricature, like a portrait where all you see is the nose. It's unflattering. Bows, bowing. My favorite means of making sounds is a bow. I have several bows and stringed instruments around here. Good stuff! Perhaps it's something visceral within me. The initial bowing sound on any instrument is wonderful, special; it has to be there, or it doesn't sound like a stringed instrument. When Kurzweil made their piano sound on the 150, they couldn't just use additive synthesis sound (additive is the most powerful way to build sounds). They had to add a hammer noise, a recorded thump, at the beginning of each note that they mixed with the rest of the partials. It's subtle, but without it, the note sounds wholly electronic. So a violin is vibrating with a note of A, but the instrument also has resonant overtones, other strings vibrating sympathetically. Did you try to create those as well? Wendy: To some extent, strings behave fairly harmonically, which is not that big a challenge. The way the harmonics vary during the course of the note--and just don't sit statically--produces a feeling of life that I like. You find clever ways of keeping something always moving, and when you go from note to note, you give each note a slightly different trajectory of the various overtones. Otherwise, it can sound dead, quite pathetic. You have to work carefully with the overtones on some of the percussion instruments, where the overtones might last only a half second. The tympani, especially, requires precise tuning of all those overtones. On Digital Moonscapes, did you place the instruments to replicate a concert hall layout? Wendy: Yes. It's all part of a later step, mixing and adding ambience, though when I'm building sounds, I always double--check it anyway. I like to have a bit of unique reverb be part of each timbre, but most of it is assigned during final mixes. You can work very dry, but you get different sound impressions later on, when hall acoustics are added. When you look at an object from a different placement, you get a different parallax, depending on where you view from. It's the same with making sounds. Yeah, I'm always aware of tricks like that. It takes discipline: you are really tweaking molecules when you get deeply into this. Sometimes you hit the edge of what one synth can do, and you become frustrated, trying to do the best with what it can do. I wish manufacturers would take the next steps to make an all-inclusive powerful, machine because in the current technology we have enough speed and power to be able to do almost anything at not too great a cost (if mass produced). But the question is, would there be anyone out there, except for the cranks and crackpots like me, who would buy such a device? Would it be commercially viable? The manufacturers tell me the answer is no. They are economics driven, and I'm art driven, or scientific-curiosity driven, or creative-intuitively driven. And it's frustrating when you've chosen to go search the field of new sounds, yet not have the tools and means to get there. Although you could have, you didn't electronically soup-up the orchestral sounds on Digital Moonscapes. Your LSI Philharmonic pretty much stands on its own. Any reason? Wendy: Digital Moonscapes was meant to be an orchestra piece that didn't use any real orchestral instruments or samples. It was a benchmark: How close could I get? During a live performance of most of the selections in 1985 I was quite surprised. The live orchestra could not play with sufficient care, finesse and feeling to match what I had done with the LSI Philharmonic, although the sounds of live instruments was lovely. It was a disappointment, showing the compromise with everything in life, I guess. Perhaps a good ensemble of good players, well practiced, could have done a closer job. So maybe I'm just tilting at a windmill here.

Nevertheless, when I hear Digital Moonscapes today, I realize it's a special little world of sound that isn't quite like an acoustic performance. It's more like looking at good computer animation, you have to view it with an eye of: "I'm in the computer graphics world, let's see what this is about." Enjoy the special things that an LSI Philharmonic can produce, not play the game of: "this doesn't sound exactly like a real violin at all." Like Pixar, I wanted to get really close, but never expected an exact match. The new Kurzweil orchestral samples that I've recently built are a better timbral match, but they are missing some of that wiry, plastic integrated behavior that a fine acoustic instrument well-played has. After all, the samples are really only recordings of acoustic sounds that you try to knit together inside of a synthesizer patch. For these two recordings, I didn't use samples: the LSI instruments were generated from scratch. Every overtone, every skritch or key tap on the attacks was done deliberately, just like Disney animation of drops of water in a pond create expanding ripples Those effects have to be studied and drawn intentionally. Snapping a picture of it is easy do to in contrast with trying to animate it yourself. So, Digital Moonscapes can be compared with Disney animation better than it can be compared with a camera or real orchestra, even while the drama or the music could be expressed either way. Does that answer your question? Interesting, but no cigar yet. For Digital Moonscapes, because it was a space theme, you could have done any number of electronic sound effects like space winds and rocket engines. But you didn't. Wendy: I had already spread my wings in those directions when I was a student, so I got it out of my system. This is a snobby thing to say, but such trickery is a little bit corny. I know the audience might love the corn, and I might be a little more successful doing it. But I was trying to go for subtlety. I may just too concerned about sophistication and subtlety. There are "gestures" on Digital Moonscapes that cannot be done by an orchestra: the most open departure from reality was that instrument in "Luna" which changes from being a violin to a clarinet to trumpet to a cello. That simply doesn't exist in real life (hmm... what would a "Strumpet" or "Clarolin" look like?). It wasn't until the next album, Beauty In the Beast, that I went the whole way and started designing instrumental timbres that can't exist at all, based on the ones that do exist.

On Digital Moonscapes, I almost heard or saw the "hand" of the conductor. It's like you were grabbing sound out and really conducting it. Was it really that fluid to produce? What program did you use to get that extra human quality to the flow and phrasing? Wendy: Thank you, Carol, I did enjoy the conducting role with the LSI performances. Of course it was much easier and more fluid in Tales Of Heaven and Hell, where I had the ability to change the tempo and make a ritard after-the-fact using MotU's Performer. The Digital Moonscapes tempos were determined beforehand, thinking it through, figuring it in my head, charting where the tempos should change, and making this extremely elaborate click track. The tempos were varied all over the place, and that is what I played to. And so it was not free and liquid; it was straight jacketed and controlled. I tried not to let it sound that way. Once more I faked an illusion of life. Of course most art uses a lot of artifice and artistry, there are tricks hiding everywhere in the best stuff. Beauty In the Beast was close to that same limitation, except the improvised passes are quite free. But a lot of it was performed against a click track as well. It wasn't until Peter and the Wolf that I could change tempos after the fact and could very nearly "conduct" my music. My last new album, Tales of Heaven and Hell, was the first album I can say I don't hear any weak phrases or tiny performance glitches. With Digital Performer, I could fix everything; if it was a little too loud or a little too bright in places, I could fix it. I could change and change and change, like an oil painting that hasn't dried. Before, it was more like drawing in India ink: once the ink is on the Bristol board, you can't change it. I no longer have unchangeable lines in my music. That's a wonderful step forward. Capital "C" ComposerCarol: This might sound like an obvious statement, but "you're a composer." Others nowadays might make up music, layer soundscapes, lay down grooves, relying on a sequencer to process the music and the rhythms. Wendy: Most recorded music now makes use of sequencing and synths. The name no longer has the limited connotation of the old analog modules which could trigger or process a few notes of different pitches--blip blip blip blop, blip blip blip bloop--all evenly spaced and dull. I have such a sequencer in my old Moog synth, it was nearly of no use for me over the years. (But the flashing lights impressed some folks!) The term sequencer generally means computer software used to store a performance of notes and gestures, allowing editing and duplicating, transposition, tempo change, a lot of such musical essentials. These sequencers are actually quite wonderful, as they act like a virtual tape recorder, but in the MIDI world. The latest sequencers have added support for audio files, too. So the notes can be individually tweaked, and the other obvious things you need for a good performance. Then it can be "played" out to the audio world, given voice by the many synths connected to it.

The self-generated and evolving sounds of the '60s and '70s sequencers were responsible for some very dull music. The newest computer packages aren't limited to crank out sausages by the yard. But all the bells and whistles on today's new sequencers can be a smokescreen, produce an illusion that real music is being made, when all it may be is a string of sounds, usually very much cliche-driven. Modern sequencers can be used as a crutch, or they can be a wonderfully powerful music creation tool. I was confused about the term, you're right. But what I meant was that "you compose." Wendy: Seems to me that music is a human endeavor. Consider mechanical pumps, a piston engine, a pendulum swinging: These are not human, and have not a whiff of musical expression about them. They represent regular repetition, not the subtle changes a good composer will make to the repetitions within a composition, the way a good performer will reinterpret a passage that repeats several times.

It's our great misfortune that these distinctions have been lost, and a couple of generations of listeners have been raised with nothing better than mechanical grooves and thoughtless looping. My distinction about the human element of music has been forgotten, lost, to the present. A dulled-down ear no longer is "put off" by quick cheap and dirty loops, TOO regular rhythmic patterns, or the elimination of real performance values. Lately I've heard complaints by younger audiences that when they hear a real performance, it's not "enough" for them. They have lost the taste for this dimension of expression and are content in a lifeless musical environment. Those of us who were not initiated into this "society of the numb & dumb" are forced to suffer through the thin gruel of musical possibilities that get served like fast food, the minimum effort to get a task done, the task of making music in this case. Wonderful new tools are applied not to Art, but to Commerce. (See, I told you I'm becoming an old curmudgeon!) But YOU Compose! Capital "C." You know what you're going for, compose along a theme, set your own parameters. You control everything and don't depend on sequencers to repeat phrases. Compose: You'd have total, ongoing control over every note, every sound, every parameter, right? Wendy: Oops! I see. The answer is YES, that's absolutely true. If I can control it, I must control it. Some very famous electronic composers brag about how untutored they are, how cool they think it is to be musically illiterate. I just get very uncomfortable about such misplaced pride. You wouldn't seek surgery from an untrained doctor, so why would want your music done by someone who doesn't know what he's doing? Composing is a balance between knowledge and intuition. Bright, good, talented people don't have to fear that that knowing too much that might inhibit their creativity. There are those who know what they are doing, but then don't spread their creative wings. Good musicians are somewhere in between. You think Mozart didn't know harmony or counterpoint? Of course he did, and he also knew what also sounded good inside his head. Joining of the intuitive with the cerebral. I guess that's my philosophy on Life and Art, although I've lifted a lot of it from good artists in the past. Can you define what your aesthetic is? Wendy: Not very well. But if I had to throw words at you, I'd like to think it includes: sophisticated, quirky, humane, witty, many layered, open ended, expansive, and inclusive. It's also both intuitive and based on rational musical and acoustical sense. Something like that. I don't take myself too seriously or think of such ideas when I'm working. Then it's just an emotional crusade, gunning for what you're hearing inside your head, hoping you come close before you have to cutoff. I seldom achieve what I'm looking for. But there are moments of getting close. Does any of this make sense?

[A loud yowling is heard.] I hear the old cat. Subi!! The poor blind dear. Let me see if I can scoop him up on my lap. Hello, baby. He's still so sweet and lovable, and he immediately started purring. Poor old guy. Wendy: It's like an old geezer's purr. He's settled in now. How do you like to compose? Wendy: Composing takes up every waking moment. When I'm not sitting down doing it, my mind is still doing it. And the best compositional ideas come when I've really spent a lot of time on it, then leave it. I distance myself from my workspace, but the mind has not gotten too far away. And suddenly the right hemisphere kicks in with something creative. I'm always sketching things. If you were here, you'd laugh. I have Post-it Notes all over the studio written with a few notes or phrases, an orchestral suggestion, a texture, a harmonic progression. I just write things down--all in the key of C (but chromatic with lots of sharps and flats) at first, to be transposed later. I don't know if I'll ever use them all, but they're interesting, so I save them. Finding Beauty in the Beast

Carol: On Beauty In the Beast, you included exotic international scales, like those from Bali, and also create entirely new scales. These days, many foreign scales are familiar to us, even if we can't name what they are. So to give the twelve tones another day in the sun, aren't these notes built around the harmonic overtones of each other? So there would be an organic reason for sticking with them...? or not? Wendy: That's where the new tunings are most interesting, exploring those which are derived from pure acoustics. Our common twelve-tone Equal Tempered scale, alas, is not one of those. Why not? Because it is a holdover of technology from the 1800s, from the old piano builders. They did the best they could, and Equal Temperament was their final compromise. It served us well, but we don't have to compromise any longer. For me the door to other scales opened when our favorite digital engineer, Stoney Stockell, found a way to give me access to the frequency tables in our custom Synergy synths (which he had largely been responsible for developing over the years). Then through trial and error I began to write several computer programs, which allow one to retune these instruments to literally anything. What are your criteria for selecting a scale to work with? Wendy: There are several things to explore. One is to have the notes blend euphoniously, which favors a Just Intonation, one with simply related intervals that blend evenly with one another. That's the best sounding way to tune a large number of instruments like the winds and strings. For more complex instruments, like the percussion instruments of Bali, or to modulate into strange keys, that is not the best way to tune. The overtones can require other schemes, and modulation takes up even more basic pitches, leading to another way to choose a scale. Or another scale might have a spicy quality to the harmonies, a tasty and novel set of sounds. It's rather like adding some hot sauce to your cooking.

There are other reasons to leave the best known tempered scale. There's been such a vast repertoire written in our so-called the twelve-tone scale, that we've kind of written it out. It's like making paintings using only four certain colors: blue, yellow, black and white. After we'd done that for three hundred years, wouldn't you want to try adding green or red, just because you might come up with a different painting? These new scales give you a simple way to sound in your own voice, not a copy of everyone else. So that's probably the most powerful reason for alternative tunings. These are reasons that should be important to a curious person. Once you establish a scale, can you hear and compose it in your head? Wendy: With many, yes of course; but there are some scales with hard-to-hear intervals. You can internalize with just a little experience what justly tuned triads sound like. Some of those spicy chords have a distinctive sound, and you can recognize them when you hear them again. There are a lot of useful scales on Beauty In the Beast. You tell me, Carol: can you recognize some of them? Yes. I can hum the piece and predict where it is going. Wendy: Excellent. The tuning that you use should be one that you can explore and prove to yourself that you're hearing it. Test-drive it. Invite a few friends over and see if they can sing it back to you. In the end, it's just a question of these four values I just stated. I hope that more people get involved with it. Many musicians now are becoming interested, but they are often younger composers who have only begun to compose. So we have no masterpieces yet, but we might get some as these composers mature. The Greeks used different tunings, but little of their music has survived. The Indians of Asia have wonderful scales, but Westerners are not interested in learning ragas. The Indonesians also have interesting scales, but now they copy our scales instead of us copying theirs. More and more of the ethnic world is using the twelve-tone scale instead of the other way around. Sad, really.

When you do your microtunings like on Beauty In the Beast, and you have perhaps 35 notes in an octave (if you do have an octave) what kind of keyboard would you use for that? Wendy: I've tried to build a fancy keyboard for that. Several times. You can see an image of one if you look in Beauty in the Beast's enhanced CD files. Open up the article I wrote for Computer Music Journal called "Tuning at the Crossroads." [see image to the right] I've tried to build one of these keyboards three times in my life. And I've never had the money and assistance to complete it. There are other versions, but they look unwieldy to me, like typewriter keys. I can't imagine using typewriter keys to perform music. Anyway, a generalized multiphonic keyboard is the way it should be done. Lacking that, I have to use the keyboards I have here, which means you use two or three of them, and tune them in various ways, mark them with stickers and try to remember what key will make what pitch. Perhaps middle C will be the only right-on pitch. All other keys on the various keyboards will be redefined. It might take three octaves of keyboard to make what you'd expect to be one octave. If you are playing Chopin, your fingers have been trained to land on thirds or octaves. But how do you train...? Wendy: You have to fight your impulses and instincts. It's often difficult because you are jumping big spaces and all. You invent some way to perform what you need. The technique is still the same, of course. It's a pain in the ass, but it's a way you get these various things, and they can sound fabulous! You can't just enter them in by number on a computer: That sounds deadly dull, mechanical--no performance. We still have not reached the phase where microtonality is more than an iconoclastic subset of music. In spite all the people who have written about it in books and journals over the years--even with pioneer Harry Partch and amazing Johnny Reinhard who organized the American Festival of Microtonal Music. There are lots of people involved with this around the world, it's just that we don't just have much communication or help from the rest of the music world, who pretend we don't exist. But you don't have to approach it from dry academic theory. Approach it from what sounds good. Many of the replicas on Beauty In the Beast sound real, to the extent that the instruments sound crude and handmade. How far did you go to get this realism?

Wendy: The Tibetan cymbals on "Incantation" were extremely hard to make, again tuning overtones. I put a whole bunch cymbal sounds in the middle of the Synergy keyboard, and rolled my fingers around to get that krrrisshh sound. It was like doing weird gestures no pianist would use, doing whatever I had to control whatever I had to play. And most of the sounds on that album are bopped out that way. Listen to the "C'est Afrique" last cue, to the harmonica. I had heard a couple of charming pieces recorded in Africa, and there were some kids playing a reedy thing, a charming, homely instrument. I had already built a good harmonica patch. So I roughened it up, microtoned, moved the volume control while hitting the notes with bit of pitchbend. The Tibetan horn brwwaannhh beginning of "Incantation" was done by using a glissando, by tuning the instrument flat. And while it was starting it up, bringing it back into tune by rotating a pitch knob. At the same time I used the Moog low pass filter so the start of that sound began filtered with a wow, and as it began sounding, I opened it up. I had the old Moog filter next to me on a stool. I twirled its knob manually, held the note down with the sustain pedal on the keyboard, and the other hand is turning the pitch bend on the keyboard. It's a foul way to play an instrument, but it worked. That's how you do these things. It was clumsy, hard to do, and I couldn't do it predictably on stage to save my life! I'd embarrass myself. But I didn't care cause I did it over until I got it right. And I saved it on the 16-track. I didn't have a hard disk audio then. If it was wrong on the tape, it was wrong. So I had to make sure I did it right. And I punched in and punched in and punched in until I got it right. Hold on. This just sunk in: You say recorded Digital Moonscapes and Beauty In the Beast to TAPE, not to computer. Man!!! Wendy: That's how those records were done. All on multi-track, just like the Switched-On albums. The tape recorder was my trusty old 3-M 56 16-track, a big 2-inch machine. Sounded real good when I made the master now, because it got recorded right from digital. And to my masters there is only that one generation of analog tape. What was it like recording just to tape? Wendy: As I mentioned, on both albums, I worked to a click track, just like on the Switched-On albums. First, take my best guesses on tempo changes, and then collect tracks. In old days, I'd do premixes as I went along. But most of the time, there was only the final mix, aside from the need to make a very simple monitoring flat mix while adding tracks, to be sure everything fit. And if it didn't, I'd have to go back and change some of them so it would, redos of single notes at times. Gee, is this where the tape splicing comes in?! Wendy: Gotta admit, this is a unique interview. You've scored another first by asking me about tape splicing. I see the craftsmanship of it. So? Wendy: Oh, jeepers. I'm blown away that you did this, actually. Wendy: It's not that big a deal, Carol. Sometimes I wouldn't trust a very tight punch-in for redoing one note or other brief spot. If I missed, it would waste hours to repair.

That's what I'd imagine. Wendy: And I would edit in blank leader tape lengths either side of bad spot, to protect the notes that were fine, and carefully avoid recording over the sections before and after these leaders. This is still the recording and performing phase. After a good retake these blank strips were edited out. The more usual splices, however, were made to connect sections that were recorded separately or to fix a stumble or remove a glitch. (There's a myriad of reasons one splices audiotape.) Then the spliced tape would get mixed down, and reverb, echo, and so forth added. Often the master stereo or 4-track (quad) tape that was thereby made would get edited again for other reasons, at least just to ensure a clean start and stop. No simple answer. You had to be very organized, and couldn't just jump in and go ahead, as you can pretty well these days. It took more discipline to get anything done, good or bad. What was the most complicated piece. Wendy: "Poem for Bali." You not only have all the individual instruments; you are forever rolling from one magic carpet to another magic carpet. The feeling is that you go from one set of instruments in one small room, say, then different instruments in a medium size room, then other instruments at a distance, then a solo. All these individual cues that had to be synchronized. It would have been much easier to do it on Digital Performer. Tales of Heaven and Hell had all sorts of scenarios like that, but in 1985 I didn't have that tool. I was synchronizing one tape on a video deck with something coming live off a synthesizer. Clumsy as all hell. You put crayon marks down and try to push the start buttons at the same time and hope for the best. But in the '90s, everything broke loose with the big steps of computer recording and editing. But since then, nothing so major has happened. So, your digital synthesis work was ahead of the digital composing work you could alter and store on the computer. Wendy: Yes. But it's funny that the computer composing people used the metaphor from all the years we worked with tape. So I could use the same skills and have the expectations. Where you wanted to edit, you slowed down the tape; the pitch and volume went down. That's what it feels like to use a tape recorder. They software designers didn't have to, but they stayed with this model. That's the way ProTools works. Which is your favorite piece of each album, and why? Wendy: No strong likes or dislikes on either of these albums. They were fairly mature projects I'm still comfortable with. Let me think because I've just heard both albums again. My favorite on Digital Moonscapes is "Genesis" on "The Cosmological Impressions" suite. Then again, on "I.C.," I love the subtle 13/8 meter. On the "Digital Moonscapes" suite, I still quite like the saxophone jazz solo on "Ganymede." The title track, the last piece I wrote, is my favorite on Beauty In the Beast. It uses a synthetic scale or two, very intricate rhythms, and a crescendo that sounds like a huge carousel. I could have easily continued in that manner for a few more movements. I'm slightly bitter that my life did not permit that then, and only now I am hoping to get back in that vein, but being a different person now, can I pick up those strands? Pushing Myself Out of the NestOn Beauty in the Beast, you print a quote by Van Gogh: "I am always doing what I cannot do yet, in order to learn how to do it." Is pioneering and innovation--or tinkering--more exciting to you than music itself?

Wendy: No. I have periodically pushed myself into a corner to see if I am going to sink or swim, to mix metaphors. Fortunately, I don't have to release the music if it's not any good. I can get away with that. I'm used to living modestly, and the tradeoff is that I am allowed, as an artist to pursue my dream. However even this gets detoured by other tasks, as the ESD remasterings have taken good chunk of life that I should have been putting in on new music. At the same time, I realize that if I do a good job preserving my older music, people won't forget it as readily as if only scratchy old LPs existed. That would have been unfair to the earlier work. So I thought, "No if you raise a child and the child has problems, you go and give your help." So that's what I've done. So that means that you can't raise any other new children at that moment. But I'm going to try now to get back to it. Where were we? Van Gogh. Wendy: Right. For me, the challenge element is hoping that I will not fall into habits so that my music will not merely repeat what I'm glib at doing. I can easily crank out the improvised stuff in Beauty In the Beast. Float a little chord in, let a high string drone, or float a tune over it. In so much music I hear these days, the composer almost always loses the ball: s/he makes far too many repetitions, or noodles around looking for a real tune. Such composers don't know where to go for gristle and contrast: the music won't have the bite and surprise you need after a mellow section. A living body contains muscle and soft tissue and bones, not only one thing. That's the way music should be, too. Diddling with a theme is not as highly demanding as the real challenge of coming up with a piece exactly right for those themes, only for that number of measures, and only right for that dramatic purpose, followed by a contrasting theme which has to move at least so many seconds before you return to the first one again in a recapitulation . . . otherwise it feels like it's a throwaway instead of a counter line. These are the important characteristics of large western musical masterpieces--and that's what we ought be trying to do always, make masterpieces.

Composer, capital C. Wendy: Yes, sure, why not? You might never achieve it, but that's the goal. To do that well, you can't just sit down and let your fingers guide you. Beauty In the Beast has a lot of diddling. Much of it was created ad hoc, on the spot--and to me, it shows, although I did later edit it into tighter shape whenever I could. Same with Land of the Midnight Sun. I was a bit horrified to realize that some of it meandered in the way that I have no patience for in New Age music, but I had to play it that way because I couldn't notate a lot of these tunings, couldn't figure out a way to play it again. It had to be done on the keyboard while I was working with it, or twirling dial knobs. It makes a kind of music that is a little bit loose and rambling, although it reaches some wonderful heights of improvisational freedom--a soaring quality that's hard to reach when you are just writing it out. So, when I saw Van Gogh's quote, I recognized something about myself, which is: I know I'm a lazy human being. If I have to repeat something for the forth or fifth time, by then the "fun" is over for me. That's when I'm tempted to take shortcuts. That's where you can lose the Art. That's where you can stop trying, and become a talented hack, or just a hack. You end up with: "great inspiration--shows promise...but...!" You should work your chops up, part of the job. You then get the melody line just right, even if you rewrite it a hundred twenty times. You do it once more to get the melody to sound inevitable, change a single note and there is diminishment. [Sings several melodic variations of "Ode to Joy"] Beethoven used his sketchbook for this. You run it over and over again to find where the heart of that theme is. The same with the harmony, the chords. Same with the rhythms. Same with the performance. You get it right. So I am always pushing myself out of the nest, even though I already know how to fly. I push myself out of a different nest. Make myself do it in a different way. And that's how you get to be more honest with yourself. This applies to writing, painting, sculpture, poetry, it's all the same creative process. So I took Van Gogh's line and applied it to my music. It fits. "All art is one." I happen to believe that, different aspects of the same beast inside us. It's our humanity, our creative human mind looking back on itself somehow. That's what creating Art is all about, don't you think? © 2001, Carol Wright, All Rights Reserved [ Site Map ] [ About Us ] [ Contact Us ] Synthmuseum.com | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||